by Mark Jay Mirsky

April 05, 2023

Featuring Excerpts From

The Diaries of Franz Kafka

Translated by Ross Benjamin

The new translation of Franz Kafka’s journals by Ross Benjamin and his extensive notes open up a new chapter for readers in English who want to understand the inner life of Franz Kafka, a writer whose work has influenced many of the major writers of 20th and 21st century fiction as well as serious thinkers in fields as diverse as philosophy, history, and sociology.

There are so many avenues of speculation about Kafka that this new edition of his journals tempt one to follow, his sexual life, his imaginative life, the tension between them, his sense of theatre and burlesque. I was struck by the Yiddish theater's power, even in its clumsy burlesque of Eastern European Jewish life, to hypnotize Kafka. Its obvious, often clumsy melodrama tickled him, the stereotypes of wealthy, ugly old men and hapless young women, the ragtag theater troupe's performances, their songs, dances, gestures.

At the theater he did not simply watch but became a participant in a private theater of sexual desire, staged in his own head. Feeling like an eighteen-year-old, he dreams himself into the bosoms of the married ladies of the troupe, even as he notes their children and husbands. Unlike the prostitutes he sought out in the brothels of Prague, he saw these actresses as young ingénues. He records how flustered and embarrassed he is by his romantic emotions in their presence, agonizing over a bouquet of flowers he sends to one (Frau Tschissik) after her performance.

In choosing selections to run on our web page I felt overwhelmed, but in conversation with Ross Benjamin he suggested that Fiction run some of the passages about Kafka’s speculation about the desert and the land of Canaan, before the Passover of 2023. The idea of passing over from one world to another, though not quite its immediate meaning in the Book of Exodus, speaks exactly to where Kafka’s thoughts were tending from 1920 to 1922, several years after the discovery in August of 1917 of his tuberculosis. His immediate journal entries in the wake of this dramatic diagnosis in 1917 show us that he felt that his body was delivering a message to his mind and that for a second time he had to break off his engagement to Felice Bauer, with no going back. Both his life and his imagination, as recorded by his biographers in his letters but even more intensely by the entries in his diaries, show how seriously the Book of Genesis was working in his mind, in the aftermath of breaking with his second engagement to Felice. Were they stimulated by the prospects of marriage to Kafka’s next two choices, Jewish women from more observant backgrounds? His fascination with the text of Genesis was certainly influenced by the classes he was taking in Hebrew, lectures he attended on the Mishnah, the rabbinical commentary that is the foundation of the Talmud, and conversations from many years earlier with the Yiddish actor Jizchak Löwy, whose recall of riddling moments of rabbinic commentary drew Kafka’s thought to his own riddles.

Before going to the moments late in the Diaries, where Kafka seems to have found himself, not in the passionate Zionist dream of his friend Max Brod but in his own whimsical reconstruction of a Holy Land, passing from a ghostly life in the desert, crossing into a normal life in Canaan, I couldn’t help asking how he got there. The trek begins in earnest, on Yom Kippur of 1911.

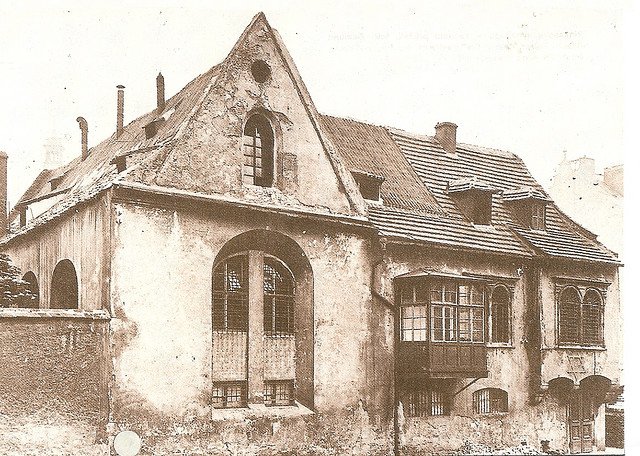

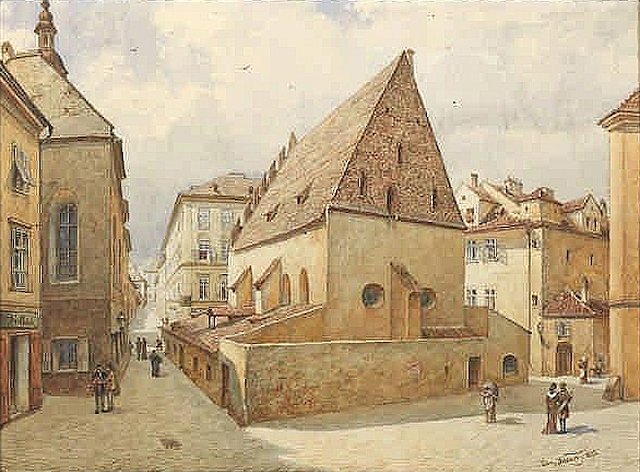

1 October Mon (Sunday 1911) Altneu Synagogue1 yesterday. Kolnidre.2 Muffled stock exchange murmur. In the anteroom a box with the inscription: “Secret donations appease indignation.” Churchlike interior. Three pious apparently Eastern Jews. In socks. Bent over their prayer books, their prayer shawls pulled over their heads, making themselves as small as possible. Two of them are weeping, moved only by the holiday? One of them might only have sore eyes, to which he briefly brings the still-folded handkerchief, only to hold his face close to the text again a moment later. The word is not actually or mainly sung, but in the wake of the word arabesques are drawn from the word, which is spun out as fine as a hair. The little boy who without the slightest conception of the whole and without any possibility of orientation, the noise in his ears, pushes his way and is pushed through the dense crowd. The apparent clerk who shakes rapidly while praying, which is to be understood only as an attempt to give the strongest possible, even if perhaps uncomprehending, emphasis to every word while sparing the voice, which wouldn’t achieve a great clear emphasis in the noise anyhow. The family of the brothel owner. In the Pinkas Synagogue3 I was seized incomparably more powerfully by Judaism.

In the Suha b[rothel] three days ago.4 The one Jewess with a narrow face, or rather that tapers to a narrow chin but is shaken wide by her hair worn in voluminous waves.

In just one short paragraph, Kafka records all the contradictions of his father’s Judaism and what seems to be the behavior of the Prague Jewish community in its major synagogue. Kafka first notices what I did as a child in the back of my grandfather’s Orthodox synagogues on regular Sabbaths, the buzz of social gossip in the back of the hall, business talk, the stock market, sports. (Though not so on the night of Kol Nidre in that synagogue when the solemnity of the fast and the fear of judgement was such that there was real weeping and crying.)

What he notices next is the Tsoddokah box, a charity box, on which is inscribed a line from the principal lament of the Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur Service, the Unetannah Tokef (the prayer of the martyred 11th century Rabbi Amnon of Mayence, whose arms and feet were cut off for refusing to convert), its cry “On Rosh Hashanah it is written down, and on Yom Kippur [a week later] it is sealed,” repeated three times in rising intensity, after each set of verses that declares “who will live, who will die, who by thirst, who by fire . . .” And then the response to this dread declaration of Divine judgment being sealed for one’s fate for the next twelve months, by the response, chanted in even greater intensity, “But Repentance, Prayer and Charity can avert the evil decree.” Even in the Altneu, I am sure the cry went up and Kafka notes its echo on the charity box in the hallway. (The word “secret” may echo the 12th century Jewish sage, Maimonides, who cited anonymous charity as the highest form of giving to the poor. Perhaps that is what the addition of word “secret” suggests on the box). None of this would have passed through Kafka’s mind at this point in his Jewish education but its poetry caught his attention.

Then he sees what is a strange sight in this congregation of mostly assimilated Jews, three whom he suspects are not citizens of Prague, but have come to this synagogue from the pious world of Jews to the east or north. These men are standing in their socks, Kafka’s limited understanding of Jews who observe the laws of traditional Judaism (which may have included many of the congregation in Prague as well) suggests that he is unaware of the Talmudic proscription about wearing leather shoes on a fast day. The sight of Jews who pull their prayer shawls over their heads seems equally novel to Kafka. He is struck by their weeping and wonders whether they are truly only “moved by the holiday.” One of them he comments skeptically “may only have sore eyes” since he keeps bringing his folded handkerchief to his weeping eyes, but Kafka adds that he keeps taking it away to go back to the book he holds and his concentration on the text.

Then something eerie occurs—he hears in their chanting not the buzz of the stock market or the general noise of the hall, but the mysterious sound of Jewish prayer echoing something very old and magical in its effect, “The word is not actually or mainly sung, but in the wake of the word arabesques are drawn from the word, which is spun out as fine as a hair.” This tremulous prolonging of the syllables, very close in a talented cantor or a congregant caught up in the deep emotion of a moment of prayer, is close to the wavering arabesques of the flamenco chant, its sound is hypnotic and Kafka registers this.

He fixes next on the little boy lost in the pushing of the crowd of men, pushed and pushing, lost without any sense of the whole of the service, or orientation. Kafka seems to be describing himself and then he catches a figure who looks like a local clerk, bobbing up and down, again in a rhythm familiar to anyone in an observant Orthodox synagogue, whose voice in contrast to the three Eastern European Jews cannot be heard above the buzz. Then he catches the family of a brothel owner, attending the service without any sense of shame or guilt. And suddenly his repugnance at the whole scene, and Kafka’s admission that he has come here hoping to find something of Judaism that has meaning to him but there are only a few fragments, recalling that; “In the Pinkas Synagogue I was seized incomparably more powerfully by Judaism.”

That last phrase echoes through the many references to Judaism throughout the Diaries, what Kafka wants Judaism to mean to him. Until the passages about the desert and Canaan in February of 1920, he will never quite surrender his sense of irony. One sees that his next reference to Judaism will be to a Jewish prostitute in the brothel owner’s establishment whom he has noted in Altneu synagogue, as if the divide between piety and practice among the Prague Jews has struck him (and his own lapses) but the idea of a spiritual Judaism that he can identify with still hovers over him.

Despite the bow to Brod’s Zionism, which Kafka is not entirely sympathetic to at this point in his life, while trying to articulate what he feels is missing in Brod’s novel Jüdinnen an earlier entry in the spring of 1911 is particularly interesting. Tracking Kafka’s developing sense of Jewish identity I hear him attempt to define what he misses. He remarks, “Jüdinnen lacks the non-Jewish spectators, the respectable opposing people, who in other stories lure the Jewishness out so that it advances against them, is astonished, afflicted with doubt, envy, horror and finally inspired with self-confidence, but in any case can only draw itself up to its full height only opposite them.” A Judaism that mirrors Kafka’s own recurring state of “astonishment, doubt, envy, horror,” needs the “verdict” of “non-Jewish spectators,” ones who remain “respectable” but oppose Judaism. It is the “respectable” opposition to Judaism from non-Jews, who judge Judaism as meaningless, which will give Judaism the power to stand up “opposite” that judgement and assert itself at “its full height.” This paradox of Kafka’s that a strong no to Judaism from the non-Jewish world will evoke a strong yes to Judaism among the mass of Jews, seems to hint at Kafka’s fascination with a mysterious Judaism proud of its Keatsian Negative capacity.

He has confided in his diary that he has been seized and wants to be seized “more powerfully by Judaism.” This is what the Diaries reveal to me as I sift his references that thread through its pages, growing more and more specific, as the music and the words of an unashamed Judaism touch him even in the melodramatic world of the Yiddish theatre to which he becomes addicted and absorbs some of the speech and culture of the Eastern European Judaism of his grandfathers. Kafka notes in the Diaries his own responses to the Yiddish plays, those that seem the more attuned to a living Judaism in their very lapses in order and logic. The stories of the rabbinic tradition that stretch back to the world of the first and second century C.E. and earlier Kafka hears from the actor-director Yitzchok Löwy. They are recalled from this luftmensch’s (man who lives on air in the clouds) early years of study in the Yeshivas of Poland. In many of the stories Kafka repeats he seems amused by the paradoxes of belief that they illustrate. They echo something of the surreal stories he will write and the strange world that the Yiddish theatre and the Talmud reflect, though he never directly identifies his fictional characters as Jewish.

He is intrigued by the information he gleans that secular studies can only be studied by a pious scholar of Talmud, on the toilet. After attending a lecture on the Mishnah at the Altneu, he goes to the home of Dr. Jeitles, one of the Prague world who is deeply learned in rabbinic literature, hoping to learn more. He retells twice the story of Rabbi Loew of Prague creating a Golem, an artificial man, out of clay. There are lines when he finds his empathy troubling and irksome. He writes in February of 1913: “What do I have in common with Jews? I have scarcely anything in common with myself and should stand completely silent in a corner, content that I can breathe.” The reduction in the last phrase seems as if he is isolating himself from the whole world and breathing painfully in his coffin.”

By way of contrast, in December of 1913, almost a year later, he writes, “The beautiful strong separations in Judaism. One gets space. One sees oneself, better, one judges oneself better.”

One of the strangest passages records his visit to a Chassidic court that meets in the rooms of an inn. Kafka’s mischievous descriptions of his father’s nose picking, and the Theosophist Steiner, echo here, but the passage registers less as sarcasm and more as a curiosity about the profane and the holy, with the innocence of childhood as its final thought.

14 (September 1915) with Max and Langer5 on Saturday at the wonder rabbi’s.6 Žižkov, Harantova ulice. Many children on the sidewalk and the steps. An inn. Upstairs completely dark, a few steps blindly with hands held out. A room with wan dim light, whitish gray walls, several small women and girls, white headscarves, pale faces, are standing around, small movements; impression of bloodlessness. Next room. All black, full of men and young people. Loud praying. We squeeze ourselves into a corner. Scarcely have we looked around a little when the prayer is over, the room empties. A corner room with two window walls, each with 2 windows. We are pushed to a table, to the right of the rabbi. We resist, “You’re Jews too, aren’t you?” The strongest paternal nature makes the rabbi. All rabbis look wild, said Langer. This one in a silk caftan, underpants visible underneath. Hairs on the bridge of his nose. Fur-edged cap, which he keeps shifting back and forth. Filthy and pure, peculiarity of intensely thinking people. Scratches himself under his beard, blows his nose through his hand onto the floor, reaches into the food with his fingers—but when he leaves his hand lying on the table for a little while, one sees the whiteness of the skin, a whiteness such as one thinks one has seen only in childhood imaginings. At that time, to be sure, one’s parents too were pure.

Biblical passages begin to filter into the Diaries in 1916, Cain and Abel, Enoch walking with God. In the years after his final break with his fiancé, Felice Bauer, in 1917, after his diagnosis of tuberculosis, his citations of the text of Genesis indicate that he has entered its text not as a commentator but as one of its characters. He speaks in February of 1920 as Adam, exiled from Paradise: “The original sin, the ancient wrong that man has committed, consists in the accusation, which man makes and from which he does not desist, that a wrong has been done to him, that the original sin was committed against him.” And later that February, as Kafka gropes towards hope, belief in life, he writes, “The power to say no, this most natural expression of the perpetually changing, renewing, dying reviving human fighting organism, is something we always have, but not the courage, although living is saying no, thus saying no saying yes.”

Kafka’s thinking about Genesis and the metaphor of Canaan and the desert appears to begin with his entries about death, how saying no is saying yes to life. At the end of these entries it is the brevity of life, however, that Kafka senses and he seems to identify with Moses and God’s prohibition about the prophet crossing the Jordan to enter the Promised Land.

The idea of living fully, of saying “yes” to life despite his diagnosis, his sense of despair, threads back into the Diaries on the 18th of October of 1921. It continues on the 19th of October with the first reference to “Canaan” and “the desert road.”

18 (October 1921) Eternal childhood. A call to life.

It is very easily conceivable that the glory of life lies ready around everyone and always in its complete fullness, but veiled, deep down, invisible, very distant. But it lies there, not hostile, not reluctant, not deaf. If one calls it with the right word, by the right name, then it comes. That is the essence of magic, which does not create but calls.

19 (October 1921) The essence of the desert road. A person who takes this road as the popular leader of his organism, with a remnant (more is not conceivable) of consciousness of what is happening. He has scented Canaan all his life; that he should see the land only before his death is unbelievable. This final prospect can only have the purpose of representing how incomplete a moment human life is, incomplete because this sort of life could last forever and yet the result would again be nothing but a moment. It is not because his life was too short that Moses does not reach Canaan, but because it was a human life. This end of the 5 books of Moses has a similarity with the concluding scene of the Education sentimentale.7

Two days later, Kafka will again find himself thinking of the world of the desert and Canaan. But to divert for a moment from the Diaries to show how striking the passage above is and how equally powerful Kafka’s identification with Abraham is in what follows I want to backtrack to a letter dated to June of 1921, four months before. I found this passage in the Letters to Friends, Family and Editors assembled by Max Brod. Kafka is writing to the young medical student Robert Klopstock.

I was never disbelieving, but surprised, fearful, my head as full of questions as this meadow is full of gnats … I can imagine another Abraham, who, to be sure, would not make it all the way to patriarch, not even to old-clothes dealer—who would be as ready to carry out the order for the sacrifice as a waiter would be ready to carry out his orders, but who would still never manage to perform the sacrifice because he cannot get away from home, he is indispensable, the farm needs him, there is always something that must be attended to, the house isn’t finished. But until the house is finished, until he has this security behind him, he cannot get away. The Bible perceives this too, for it says: “He put his house in order” And Abraham actually had everything in abundance before: had he not had his house, where would he have reared his son, into what beam would he have stuck the sacrificial knife?

In the letter Kafka goes on to imagine multiple Abrahams all echoing his own situation.

. . . the above mentioned Abrahams, they stand on their building sites and suddenly are supposed to go to Mount Moriah. Possibly they do not even have a son and are called on to sacrifice him. These are impossibilities and Sarah is right to laugh. All we can do is suspect that these men are deliberately not finishing their houses and—to name a very great example—are hiding their faces in magical trilogies so as not to have to lift their eyes and see the mountain that stands in the distance.

Finally there is another Abraham. One who certainly wants to carry out the sacrifice properly and in general correctly senses what the whole thing is about but cannot imagine that he is the one meant, the repulsive old man and his dirty boy. He does not lack the true faith, for he has this faith; he wants to sacrifice in the proper manner, if only he could believe that he was the one meant. He is afraid that he will, to be sure, ride out as Abraham and his son, but on the way will turn into Don Quixote … the world will laugh itself sick over him. But it is not the ridiculousness itself that he fears . . . he chiefly fears that this ridiculousness will make him still older and more repulsive, his son dirtier, more unworthy to be really summoned. An Abraham who comes unsummoned!

Kafka is reveling in this “repulsive” Abraham and his either non-existent boy, or if existent, dirty and getting dirtier as they slouch, unsummoned to a distant mountain, where only a polluted sacrifice of his “dirty” son, laughed at by the whole world, could be enacted. This is obviously Kafka’s joke on his own identity as a demented, hallucinating Abraham. It is a performance for the young Doctor Klopstock.

The passages about Abraham, in the letter to Klopstock, are months before Kafka’s musing about the patriarch in October. To return to the Diaries: On the 21st of October, after an “afternoon on the sofa,” Kafka is dreaming again (but to himself) within the text of Genesis, just before the angels come to Abraham’s tent as messengers and turn into the single God of Abraham to announce that Sarah at the age of ninety will bear a child.

21 (October 1921) Afternoon on the sofa.

It had been impossible for him to enter the house, for he had heard a voice saying to him, “Wait until I lead you.” And so he was still lying in the dust outside the house, even though by now everything was probably hopeless (as Sarah would say)8

Ross Benjamin’s note identifies this as an allusion to Genesis and Sarah’s hopelessness at bearing children.

Kafka’s reading seems to be based on his imagining Abraham outside the tent, in the dust of the desert, hopeless, when the strangers come as messengers of the Holy One. Has Abraham been forbidden to go in to try to engender an heir for the both of them in the body of Sarah? Was this a stretch of time of some years in Kafka’s mind, preceding the approach of the angels, and the voice of the Holy One asking Abraham why Sarah laughed at the idea of a child? Kafka seems to be writing not an interpretation of the text but as Abraham unable to sleep with Sarah because of a Divine prohibition. Abraham in Kafka’s version of Genesis has heard long before the angels arrive a voice telling him not to sleep with Sarah until he is instructed to do so. When did this happen? Was it after his wife, Sarah, told him to sleep with her maid, Hagar? Kafka’s speculation on the Biblical text opens up any number of other possible stories. Was it the laugh of Sarah that the Holy One was waiting for before the Holy One told Abraham, or implied, that he should now enter his tent and perform coitus?

Has Kafka in fact been waiting for the voice throughout his life until this moment—not just to marry but beget a child?

28 (January 1922) A little faint tired from sledding,9 there are still weapons, so rarely wielded, I have such difficulty reaching them, because I don’t know the pleasure in their use, didn’t learn it as a child. It is not only “my f.’s10 fault” that I didn’t learn it, but it is also because I wanted so to destroy the “calm,” to upset the balance and therefore could not let someone be newly born over there when I was taking pains to bury him over here. Admittedly, I return to “fault” here too, for why did I want out of the world? Because “he” didn’t let me live in the world, in his world. I cannot judge so clearly now, to be sure, for now I am already a citizen in this other world, which is to the ordinary world as the desert to cultivated land (I have been wandering for 40 years from Canaan), look back as a foreigner, am admittedly the smallest and most anxious in that other world too—I have brought this with me as my patrimony—and am capable of living only by virtue of the special organization there according to which even the lowliest there can undergo lightning-like elevations though also sea-pressure-like thousand-year shatterings…. Didn’t my f.’s power make the expulsion so strong that nothing could resist it (it, not me)? Admittedly, it is like the wandering in the desert in reverse with the constant approaches to the desert and the childlike hopes: (especially with regard to women) “perhaps I will stay in Canaan after all” and in the meantime I have long since been in the desert and they are only visions of despair especially at those times when I am the most wretched of all even there and Canaan must present itself as the only land of hope, for there is not a third land for human beings.

For a brief time before his death, his last fiancé, Dora Diamant, would dissolve his hesitations about marriage, and with her mastery of Hebrew and agility in Yiddish allow him to dream not of Canaan, but of a normal life lived in a Canaan or Palestine that Zionism had transformed in part into a Land of Israel. Like Moses, he would not be able to enter it, but he could dream of a humble life there with Dora as a “land of hope.”

1. Located between Maislgasse and Niklasstraße, the “Alt-Neu-Synagoge” (Old New Synagogue), also known as the “Alt-Neuschule,” is Prague’s oldest synagogue.

2. Kafka made an error in the subsequent addition of the day of the week. Kol Nidre is the name of the introductory prayer on the eve of the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur); in 1911 it fell on Sunday, October 1. Kafka’s uncertainty about the date is also made clear in the manuscript by the multiple corrections of the date.

3. Located on Josefsgasse adjacent to the old Jewish cemetery.

4. B. for brothel. The Salon Šuha (U Šuhů) on Benediktgasse was among the more well-known Prague establishments. It is mentioned in Jaroslav Hašek’s 1921–23 novel The Good Soldier Švejk.

5. Georg (Jiří Mordechai) Langer (1894–1943) had devoted himself to Eastern Jewish Chassidism and in the years 1913 and 1914 temporarily belonged to the court of the Rabbi of Belz, one of the wonder rabbis of the Orthodox sect, who had to leave Galicia with his adherents when the war broke out. Shortly after being called up for military service, Langer was discharged for “mental disturbance,” because he refused to give up his Orthodox way of life (sidelocks and beard, clothing, etc.). For a brief time afterward, he lived in Prague again before returning to the Rabbi of Belz, who was now living in exile. At that time—most likely through his distant relative Max Brod—he became acquainted with Kafka.

6. Max Brod recalls: “At that time, together with my Kabbalist friend Georg Langer, I spent a lot of time at the home of a wonder rabbi [Brod’s annotation: the Rabbi of Grodeck], a refugee from Galicia who lived in dark, unfriendly, crowded rooms in the Prague suburb of Žižkov. . . . It is notable that Franz, whom I took with me to one of the ‘Third Meals’ at the end of the Sabbath, with its whispering and Chassidic singing, actually remained quite aloof” (FK 137).

7. Max Brod reported that he and Kafka had already read Gustave Flaubert’s Education sentimentale together in a French edition in the first years of their friendship (FK 54). Kafka probably read the volume L’éducation sentimentale. Histoire d’un jeune homme (Paris, 1910), which was among the books in his possession at the time of his death, during his stay in Jungborn. See June-July 1912 Trip, pp. 559, 561, and 562.

8. An allusion to Genesis and Sarah’s hopelessness of bearing children.

9. In late January 1922, Kafka wrote to Robert Klopstock: But apart from that I can go sledding and mountain climbing, high enough and steep, without particular harm, the thermometer is disregarded (Br 370).

10. His father’s (Hermann Kafka).

Notes and select quotations from THE DIARIES of Franz Kafka, translated by Ross Benjamin. Reprinted by permission of Schocken Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Translation copyright © 2022 by Ross Benjamin. Copyright © 1990 by Schocken Books.

Mark Jay Mirsky, professor of English at The City College of New York published his first novel, Thou Worm Jacob, in 1967, succeeded by Proceedings of the Rabble, in 1971, Blue Hill Avenue in 1972, and a collection of short novellas and stories, The Secret Table, in 1975 with a cover by Donald Barthelme. In 1977, Mirsky published My Search for the Messiah, a collection of essays including sketches of major Jewish thinkers: Harry Wolfson, Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, and Gershom Scholem.

Read More →